Classic CRT TVs have become de rigeur in the retro scene as the true way to experience retro games “the way they were designed”. But there’s a lot of benefits to modern TVs; they’re lighter, usually bigger, and there are a lot of upscalers that give really good pictures. But then you give up peripherals like light guns, that are permanently tied to the television’s timing. Or are they?

This post was originally published on Nicole Express, my personal blog.

The humble lightgun

For the purposes of this blog post, let’s set out some ground rules.

- When I say “lightgun”, I mean the guns that were shipped for the Famicom and the Nintendo Entertainment System. Different guns worked different ways.

- When I say “LCDs”, I pretty much mean all modern television screens. In fact, even the short-lived generation of HD widescreen CRT TVs share this problem.

But what problem? Well, I’m getting ahead of myself.

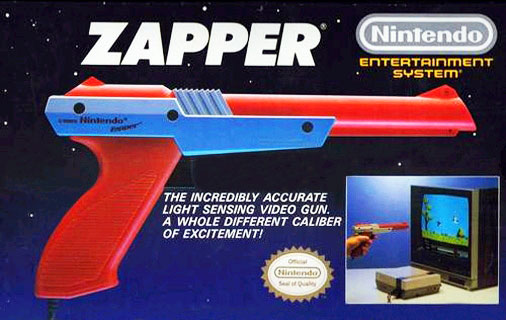

The Zapper was the western packaging of the Famicom Gun. Either way they work the same inside, just one looks like a raygun and is fondly remembered, and one looks like a realistic gun and doesn’t seem to have been nearly as popular. Make your own cultural assumptions.

This is one case where Nintendo drew on their history. They had actually been making light gun games since 1973’s Laser Clay Shooting System and toys before that. The exact details of each system they’ve used varied a bit, but the basic concept doesn’t differ too much.

The Zapper gun consists of a trigger and a photodiode, basically a simple light sensor. When the trigger is pulled (on the NES and Famicom, this is a falling edge from 5V to 0V), the game reads the signals from the photodiode to determine what happened. (Interestingly, on the NES and Famicom, the Zapper trigger and photodiode have their own pins, and aren’t read serially like the controller is)

The thing to stress is, the photodiode is literally one bit of information. All the game can figure out from that is whether there’s light going into it at any particular time.

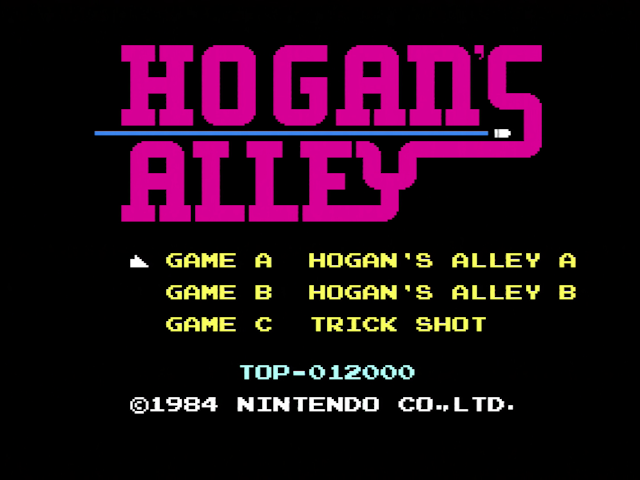

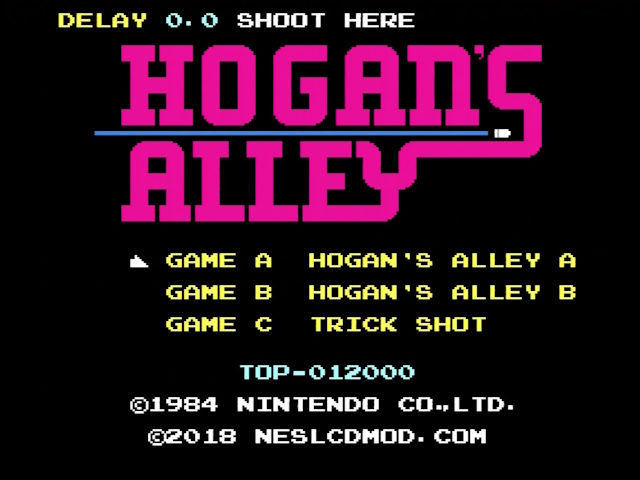

Let’s use a concrete example– Hogan’s Alley.

Game mode “A” is a simple shooting gallery. You are given three figures, and have to make a split-second decision which of the three you should shoot.

So there’s your problem. The photodiode gives you one bit of information; that’s not nearly enough to distinguish the three characters. After all, they all use similarly colored pixels, not that the photodiode even has color information.

Well, you might already know the answer. The photodiode only provides one bit… at a time. By setting a clever number of frames, you can extract more information.

First, a black frame. This helps prevent cheating; at this point, it knows that your gun is pointed at a TV which is turned off. Then, a succession of frames that are mostly black, with white targets. Each one corresponds to one of the figures on screen. Since this all happened so fast, your gun is still pointing at the same place it was when you pulled the trigger.

Why does it only check two? It thinks it figured out who I shot. And there’s the problem; I was pointing the gun at an LCD TV; a small widescreen monitor I keep next to my desktop alongside a CRT as a test setup.

The problem is, a CRT TV draws frames in real time. The Nintendo knows that when it draws a frame, that frame drawing is corresponding with the moving electron beam of the television in real time. In fact, NESdev claims that the photodiodes use have their signal die in as short as 10 scanlines, so the game needs to check more frequently than the 60Hz clock that usually governs an NES game.

What the Famicom doesn’t expect is that the screen could be late.

Resolutions and frequencies

Pretty much all analog video signals, RGB or otherwise, are imitating the raster of a television. That is to say, it assumes there is only a dot being drawn on screen at a time, and it provides signals that are timed as that dot moves across the screen.

This works perfectly fine for a CRT television that’s tuned to expect a line frequency of 15kHz and field rate of 60Hz, like most standard-definition televisions in Japan or here in North America. However, this assumption breaks down very fast. Those 60Hz monitors almost certainly can’t even handle PAL video, with the same line frequency.

The same issue applies to VGA CRTs and HD CRT televisions, whose native line frequencies are much higher. Non-CRT televisions don’t even draw the screen in the same way! And oftentimes even a digital input signal won’t be at the same resolution as the panel in the screen.

So every single modern TV has a scaler inside. These can be particularly bad at handling 240p, but pretty much every signal that comes into a television will need some processing to match how it works inside.

And that’s why your lightgun won’t work on an LCD television. By the time the screen shows the white frames, the game already thinks you lost and went out to do something else. This is true even the Framemeister scaler I’m using here; as its very name implies, it’s a frame-buffer, so before even the TV has seen the signal it’s a frame behind.

Note that even “Game Modes” can’t get the lag down to the zero it needs to be here. The signal just isn’t suitable for your television. It must be processed.

So… that’s it?

Obviously not, didn’t you read the title of the post? You can still play Wild Gunman! The GAME A mode, anyways. It turns out this doesn’t actually go through the dance above; there’s only one thing on screen. It just checks your timing. But be warned; you can still lose!

But what if you want to play a better different lightgun game? Even the other game modes on Wild Gunman won’t work like this.

Here’s the clever thing. While your television is definitely displaying the screen late, if it’s a decent scaler, the lag is going to be constant. If it’s constant, it can be predicted. If it can be predicted, the game can be reprogrammed to wait that long.

Now, you might say, that seems like a lot of work! And it is. But thankfully, I don’t have to do it– the folks at LCDMOD already have. Unfortunately, this is a pretty considerable mod, so patches are mostly limited to the earlier titles.

Tools of the trade

It’s worth noting that Nintendo, which had been making light toys for awhile, was already wise to ways people cheated. One way they got around that was to use a photodiode that was most sensitive to the 15kHz light of a CRT television electron beam. That way, in addition to the black frame check above, it wouldn’t work to just point the gun at a lightbulb or other light source.

Of course, an LCD TV doesn’t put off a 15kHz light. Thankfully, the solution to this is pretty simple. Just use a third-party light gun– Duck Hunt is legendary enough that they still make these things. You don’t need to buy Hyperkin’s model; I used a “Tomee” branded one and it also had a compatible photodiode. In this case being cheap is better.